No products in the cart.

Vol.9 Water Cooled Condensers & Cooling Towers

Author Mike Creamer, Business Edge Ltd

AIR CONDITIONING TECHNOLOGY – PART 9

Water Cooled Condensers & Cooling Towers

IN Vol 8 month’s article we looked at how Air Cooled Condensers are used to transfer the total heat of rejection from the air conditioning system to ambient air. This month we consider alternative means of heat rejection.

WATER COOLED Condensers

This section deals with the application and use of water-cooled condensers (shell and tube type) in the refrigeration cycle. Earlier in this series we outlined the thermodynamic process by means of a Pressure-Enthalpy diagram, the primary functions performed by the condenser being de-superheating, condensing and sub-cooling.

Water-cooled condensers are available as a separate component, for field use, within site built equipment or as a replacement item following a failure. Factory built packages will normally incorporate the condenser fitted within the complete unit. Water piping and associated controls to the vessel are then installed on site.

FIGURE 1

The Bitzer shell and tube cleanable water-cooled condenser employs the latest development in high efficiency condenser tubes. Tubes are integral – fin copper, roll expanded into thick tube sheets, are removable and can be replaced in field service. The cast iron heads are also removable. Marine units are available for seawater applications with the appropriate material specifications.

FIGURE 2

FIGURE 3

FIGURE 4

Figure 4 shows the general arrangement of connections to a typical water-cooled condenser.

Selecting and sizing a condenser is usually a straightforward process using manufacturers published data. The following information is required before selection tables can be entered:

1. Total heat rejection.

2. Evaporating temperature.

3. Condensing temperature.

4. Entering water temperature.

5. Fouling factor required. (*)

* This factor allows for the ‘fouling’ of tube surfaces on the water side, by sediment or deposits and selection is not usually made on a clean basis.

Water piping to the vessel should be arranged in order to maintain constant condensing pressure where the condenser supply water temperature varies. For cooling tower applications, a three way-diverting valve is normally used to modulate the amount of water flowing through the condenser. An alternate, but less accurate means of controlling tower water is with a tower fan thermostat. In all instances, it is recommended that a strainer be installed upstream of the water regulating valve to protect the valve from seizure. Vessel connections and positioning varies according to manufacturer and detailed information should be sought at the design stage.

Condenser vessels should be mounted horizontally and in a level plane. Adequate space (equal to the vessel length) should be provided at either end of the vessel to permit tube removal should this become necessary. Cleaning access must also be considered.

Good refrigeration piping practice must be followed to assure leak free connections. After the refrigeration pipework is installed, the entire system must be pressure tested for leaks. The system must then be evacuated and moisture free before it is charged with refrigerant. The system design and installation must be carried out in accordance with current practice and regulations.

Since the long term performance of condensers will be adversely affected by poor water conditions, it is recommended that an analysis of the condenser water be made and a treatment system provided when installing the condenser. Problems to be addressed include scaling of the condenser surfaces corrosion, algae or slime. Those who are qualified and competent to prescribe what is required should only undertake water treatment.

Freeze prevention is necessary as severe damage can be caused to the structure of the vessel. If the condenser will be subjected to ambient temperatures below 0ºC, it must be protected from freezing. If the condenser is to be idle during cold weather, it is essential that it be drained of all water. It is possible to freeze tubes, even in warm weather, by improper maintenance procedures. If refrigerant is stored in the condenser, and gas is removed from the condenser, allowing pressure to drop below the saturation value of 0ºC, water in the tubes can freeze. To avoid this, when transferring refrigerant, always have condenser water flowing and / or remove liquid refrigerant before releasing pressure. Only suitably qualified and certified persons should engage in this work.

Condenser tubes should be cleaned periodically to assure optimum condenser efficiency. Frequency of cleaning will depend on individual water conditions and the water treatment system employed. A suitable cleaning schedule should be determined and included in the overall maintenance programme.

Selection Procedure

This will vary between one manufacturer and another. The following procedure is used to select Dunham Bush Water Cooled Condensers:

THR = Total Heat of Rejection (350 000 Btu/hr / 102.6 kW)

EWT = Entering Water Temperature (80 Deg F /26.6 Deg C)

SDT = Saturated Discharge Temperature (105 Deg F / 40.5 Deg C)

LWT = Leaving Water Temperature

AT = Approach Temperature

1 Add required fouling factor to total THR

For normal cooling tower applications where a fouling factor of 0.000176 W/m2 K (0.001 Btu/hr ft2 R) is specified, add 21%.

Corrected THR = THR x 1.21

= 350 000 x 1.21 = 423 500 Btu/hr

2 Calculate Approach Temperature:

Approach Temperature = SDT – EWT

= 105 Deg F – 80 Deg F = 25 R

3 On appropriate capacity graphs, plot corrected THR against Approach Temperature and read required water flow rate and pressure drop.

FIGURE 5

4 Calculate the Water Temperature Rise:

THR 102.6 kW

= = 4.62 K

4.187 x Flow Rate (l/s or kg/s) 4.187 x 5.3 l/s

5 Calculate Leaving Water Temperature:

LWT = EWT + Temperature Rise

= 26.6 + 4.62 = 31.22 Deg C

Note: The un-corrected THR is used when calculating the water flow rate.

COOLING TOWERS

Many years ago, numerous air conditioning and refrigeration systems rejected heat to a continuous stream of water, either from a natural body of water or purchased from a water utility supplier, which was then discharged back into its source. Increased water supply costs and problems with higher temperature discharge water severely affected these methods.

To overcome these problems, a continually recirculating mass of water absorbs heat from the Water Cooled Condenser and is then passed through a cooling tower in order for the heat energy to be removed thus allowing the water to return to the condenser at the correct temperature.

Process heat exchangers can also be connected to cooling towers to facilitate the removal of heat energy from a process plant installation.

The water consumption rate of a cooling tower system is only approximately 5% of a once-through method, making it the least expensive system to operate compared with purchased water supplies.

The factors to be considered in sizing a cooling tower are the heat load, approach temperature and wet bulb temperature. The heat load in determined by the process duty, the local climate determines the wet bulb temperature and the remaining factor, approach temperature, is determined by how low the water has to be.

The driving force for heat transfer is the difference in enthalpy between the air contacting the water surface and the bulk air stream. The enthalpy content of moist air is the summation of the sensible heat content of both the water and air present, the latent heat of the water vapour, plus (for non-saturated mixtures) the superheat of the water vapour.

At a given temperature, air is capable of co-existing with only a limited quantity of water vapour, the amount being determined by the partial vapour pressure of the water vapour in the mixture. If the pressure of the vapour in the air is lower than the atmospheric pressure then evaporation can take place. The quantity of water vapour present in the air is small, typically 5.0 and 20.0 grams of vapour/kg of dry air (g/kg).

Wet Bulb Temperature:

The temperature to which the air would have to be cooled in order to reach 100% saturation with moisture.

Approach Temperature:

The difference between the required cooled water temperature and the wet bulb temperature; determines how difficult the duty is. A small approach means a larger cooling tower.

FIGURE 6

Heat load:

A function of the quantity of water to be cooled and cooling range. For a fixed heat load, various combinations of range and approach will be possible; the graph in Figure. 7 shows the effect on tower size. A large range and small flow results in a smaller cooling tower.

FIGURE 7

A cooling tower cools the water by using a combination of heat and mass transfer. The entering water is distributed through the tower via spray nozzles over plastic fill packing, which provides a large water surface area to be exposed to ambient air. The ambient air can be circulated naturally using available wind currents, or using mechanical fans (a mechanical draught tower is far more dependable as it uses a known volume of air, as opposed to natural draught which is generally used on large hyperbolic towers for electricity generation).

Most of the heat is transferred to the air through evaporation of a portion of the circulating water (approximately 1% for every 8°C range), the remainder through sensible heat transfer. The difference in temperature between the water entering and leaving the cooling tower is known as the cooling range. Accordingly, the range is determined by the cooling tower heat load imposed by process and water flow rate, not by the size or capability of the cooling tower.

Mechanical draught towers are classified as either “forced draught”, where the fan is located in the incoming ambient air stream, or “induced draught” which has the fan situated at the tower exit position to draw the air stream through the tower. Forced draught towers are characterised by high air entrance velocities and low exit velocities, which can make them susceptible to recirculation, giving instability in performance.

Induced draught towers have an air discharge velocity of from 3 – 4 times higher than their air entrance velocity, and the location of the fan in the warm air exit stream provides excellent protection against the formulation of ice on the mechanical components. Induced draught towers can be used on installations as small as 5 m3/hr and as large as 150 000 m3/hr.

Tower types are also classified by airflow. In a counter-flow tower, air flows vertically upwards through the heat transfer medium (plastic fill packing), counter to the downward flow of the water. In a cross flow tower the movement of the air through the fill is across the direction of the waterfall. Each type of tower has distinctly different fan power and pump head energy consuming characteristics.

Figure 8 – Crossflow Cooling Tower with propeller fan – Induced Draught configuration

Figure 9 – Counter-flow Cooling Tower with centrifugal fan – Forced Draught configuration

Energy is absorbed in driving the fan necessary to create proper air movement through a cooling tower. The pump head of a cooling tower also contributes to the expended energy in the operation of the condenser water pump. Therefore, manipulation of one or both of these power consuming aspects as a means for adjusting for changing loads or ambient conditions should have some beneficial effect upon the towers energy requirements. Deciding which of these aspects to control and how to do it will depend primarily upon specific characteristics and restrictions of the condenser / chilled water system.

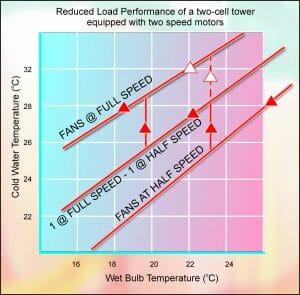

On a cooling tower serving a process, which benefits from colder water temperatures, any attempt at fan manipulation should only be made when the cold water temperature reaches a level that results in optimum system energy use, which can vary with system design. Having determined the level at which control of the tower’s cold water temperature will be most conducive to total system power reduction, several energy efficient methods to achieve this control are available. The most commonly used methods follow in general order of increasing effectiveness:

Fan Cycling: At any time that the tower is capable of producing a water temperature colder than the control level, the fan can be shut off for the period of time it takes the water to build back up to the control point. A thermostatic device can be used to accomplish this cycling automatically, which works well provided that there is a sufficient spread of temperature available between the make and break levels (differential) to ensure that the fan motor windings insulation does not become overheated by an excessive number of starts per hour.

Fan Capacity Variation at Constant Speed: To achieve a balance between the operational requirements of the chiller and the wish to conserve cooling tower fan energy, control of fixed speed fans seems to be limited to a series of speed steps, resulting in either an under or over achievement of the goal being sought. The control effort would be much simpler if the fan capacity could be varied such that the tower would track the load at a constant cold-water temperature. The means to accomplish this result exists in the form of automatic variable pitch propeller fans, designed specifically for cooling tower use. These can be retrofitted to existing installations.

Progressive Variation Of Fan Speed: The load of a cooling tower fan can theoretically be made to track the curve indicated in Fig.14 by the use of a frequency modulating device (power inverter). The ability of these controllers to vary frequency results in a capability to infinitely vary the fan speed. Total variability is restricted on cooling tower applications, which is a characteristic of the fan itself. There is an obvious need to restrict over speeding, and most fans do have at least one critical speed so it is wise to predetermine what this critical speed is. Most frequency modulating devices permit avoidance of selected frequencies, so that critical speeds will be passed without risk of extended operation at those speeds.

Fan control is, without doubt, extremely beneficial in varying the thermal performance level of a cooling tower when applied properly. However, misapplication can also have a detrimental effect upon the ultimate energy costs of some air conditioning systems. An induced draught crossflow cooling tower can achieve 10 – 15% performance at zero fan speed due to natural air movement, while the enclosed nature of a forced draught tower prevents this advantage.

Today’s wide range of open and closed circuit, factory assembled evaporative cooling towers are designed with a major consideration to ease of access for routine maintenance and servicing. All separate components are easily removable, with some units having detachable panels for added admission to motors etc.

Evaporative cooling systems are without doubt the least expensive cooling technique, whether applied to Air Conditioning, Refrigeration or other Process Cooling Applications. Dry air coolers are not only larger, heavier and noisier than evaporative coolers, but they demand much more fan energy and a far higher air intake, plus having a higher initial outlay cost. Evaporative cooling towers are ideal in Air Conditioning systems partly because they can achieve lower temperatures from a given ambient than other evaporative or dry air equipment. User maintenance however, is extremely important; as with any application, to contain bacteriological dangers.

The evaporative cooler is an efficient alternative to the cooling tower, which compares quite closely in terms of performance, but both are well ahead of the dry air cooler, as seen below.

FIGURE 10 and 11

Comparison for Cooling tower, evaporative cooler / condenser and dry air cooler, applied to the same heat load

For / Against

Tower Lowest temperature Water treatment

Lowest capital cost Maintenance

Smallest size / weight Water supply / drain

Low energy costs

Evaporative Cooler and Lower temperatures Higher capital costs than tower

Condenser Lower capital cost Higher temperature than tower

Smaller size / weight Water supply / drain

than dry cooler

Lower water treatment costs

than tower

Low energy costs

Dry Cooler Little maintenance Highest capital cost

Little water treatment Highest running cost

Electro / mechanical Highest temperatures

services only Greatest weight

Largest area

Most noise

Most controls

Highest energy cost

NEXT MONTH: Vol 10 – Expansion devices